PrEP: for whom are these pills?

From the Incidence 0 Archives

📢 First published: 22-Mar-2011

☑️ Reviewed: 31-Aug-2024

The results of the iPrEX study announced in November 2010 have brought some hope back into the field of HIV prevention. The clinical trial, which investigated the effectiveness of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) mostly amongst men who have sex with men (MSM), showed that daily dosing of the anti-HIV drug Truvada (Tenofovir/Emtricitabine) was safe and could reduce the risk of HIV infection by 44%.

Since the release of the results, the study has been under the limelight in the media but also at a number of conferences and within the advocacy movement where it is raising several questions and challenges. Amongst these, that of who would benefit most from this new HIV prevention approach is highly relevant as a global roll out is yet unconceivable.

Concerned that Truvada, which is already being used to treat people living with HIV, could be prescribed incorrectly by health professionals and used inappropriately by potential PrEP users, the CDC promptly issued an interim guidance aimed at service providers and identifying MSM at high risk as the first target for PrEP. In this regard, the CDC defined MSM at high risk of HIV infection by:

- Inconsistent condom use

- Number of partners

- Concurrent partnership in geographic area with high HIV prevalence

Though rational, this definition raises a number of questions regarding its usefulness in the real world. Inconsistent condom use is becoming a growing constant amongst MSM. Setting a threshold for the number of sexual partners warrants considering PrEP is also challenging. Will it be more than 4 partners in the last 6 months, the iPrEX enrolment criteria, or last 3 weeks, as reported by the participants in the study? Concurrency is very relevant but it is surprising that geography prevailed over ethnicity since recent surveillance data supported further that new infections in the US occurred mostly amongst young Black and Latino men.

The CDC estimated that 275,000 men in the US could be considered as “candidates” for a conversation about PrEP. The choice of word is welcomed, as it should be clear that PrEP is not for everybody (PrEP requires high adherence to work, this means taking the drug everyday for it to work as shown in a subgroup analysis of the iPrEX study). Some advocates have often pointed out that a large number of HIV infections occurred whilst MSM were in a stable relationship, which is counterintuitive with the concept of high risk of HIV infection.

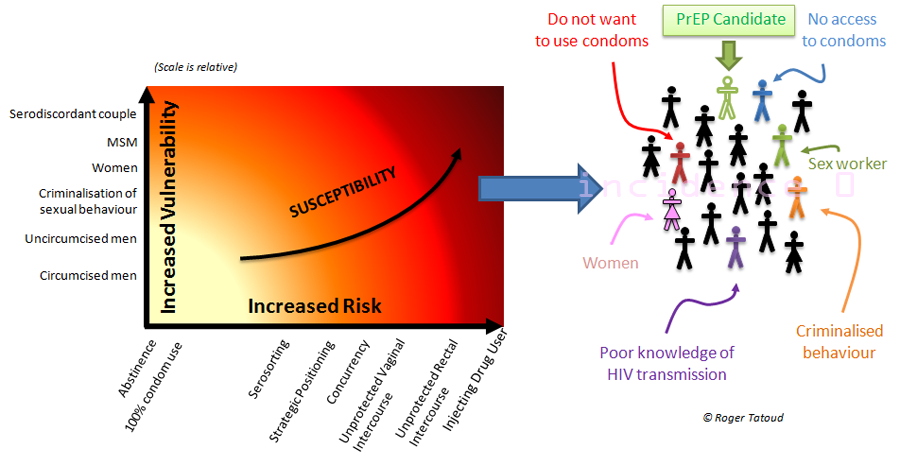

The current prevention construct of “high risk population/individual" may be misleading and could explain some of the confusion and difficulty in deciding who should be considered for receiving PrEP or having a conversation about it. As currently defined, it is a reductionist understanding of the diversity of individual circumstances that lead to different behaviours and practices and potentially HIV infection. A different approach would consider HIV infection as the result of the combination of at least three variables: vulnerability, risk and time which altogether define an individual's susceptibility to HIV infection.

Vulnerability is deterministic, intrinsic, biological, but can also be framed by social and cultural factors such as criminalisation of sexual behaviour, gender imbalance and so on. Women are more vulnerable to HIV infection than men, uncircumcised men are more vulnerable than circumcised one. However, a young man in South Africa is more vulnerable to HIV than a “glossy magazine reader” woman in New York. Vulnerability is neither linear nor fixed but results of a combination of features at a certain point in time.

In contrast, risk is defined by behavioural features. Receptive unprotected anal intercourse with an HIV+ person carries more risk of HIV transmission than insertive vaginal intercourse with an HIV+. Condoms, when used, dramatically reduce the risk of HIV transmission or acquisition. As with vulnerability, the overall risk is the result of a combination of a number of factors. Some combinations can result in higher or lower risk than each individual behaviour considered separately.

Then there is the time factor. Individuals can and do change their behaviour in the heat of the moment or as circumstances in their life change, which in turn affect their overall susceptibility to HIV infection.

Those who would most benefit from PrEP are those with “high susceptibility” defined as a combination of high vulnerability and high risk behaviour and identified on the right side of the diagram (above). It should be obvious that this group (which does not represent a particular population or community) is largely heterogeneous, and includes both men and women, suggesting a potential usefulness of PrEP for HIV- women in a serodiscordant couple wishing to conceive.

Whilst focussing on MSM, there is a need time and again to understand and factor the broad diversity of this group and of the many contributing factors affecting each individual's susceptibility to HIV infection. In many case, PrEP would not be the first answer to prevent HIV transmission.

If a population for PrEP needs to be identified, it will not be homogeneous or fit nicely into a semantically defined box and a solid algorithm will be needed to capture the diversity of its potential recipients. This will go beyond number of partners & condom use. At the end of the day, PrEP may not be for those who are at high risk or highly vulnerable and this somewhat echoes Robert Grant views expressed at CROI that "The criteria for deciding to give someone PrEP is that they ask for it".

Finally, I’d like to recall Susan Buchbinder’s words also at CROI that we need to ensure that those who need PrEP most get it. The crucial word here is “need” which point towards PrEP being a personal HIV prevention option which then beg the question: should we be able provide PrEP to those who need it most, will it be on a scale that it will make a difference in the HIV epidemic? But that is a very different question.

- Following the result of the iPrEX trials, the feasibility and speed of a global PrEP rollout was a significant concern for communities and advocates.

- 14 years after iPrEX, PrEP remains largely underutilized. In 2022, CDC estimated that 1.2m people in the US (compared to 275K in 2011) could benefit from PrEP and that only 36% were prescribed it. Access remains a teething problem - See PrEPWatch

- Ultimately, PrEP roll out repeated what had happened with the roll out of HIV treatment and prefigured what is currently happening with the roll out of Long Acting PrEP.

- However, PrEP is definitively making a dent in the HIV epidemic in some places (for example in the UK), and pericoital dosing (or PrEP "On Demand") has proven as effective as daily dosing in male.

- Despite progress, access to effective medicines, even for those who contributed to their development, remains limited. Initiatives like the Medicine Patent Pool are pivotal to improve access through patent pooling and the fostering of public-private partnerships for better public health management of intellectual property.

- The development of Lenacapavir, a 6-monthly injectable is welcome, prompting calls for long-acting ARV to be made available promptly for both prevention and treatment.

- However, there is a risk that Lenacapavir, as a better and more profitable drug for the industry to develop and focus on, could displace Cabotegravir, and with that current efforts to improve access to the latter. But Lenacapavir may also facilitate sub-licensing of Cabotegravir as a less attractive product fro the industry.

- The criteria for deciding to give someone PrEP remains that they ask for it.